Jumping out of a perfectly good airplane, while in flight, without a parachute is generally not recommended. Strangely, it's exactly what happens in a lot of corporate lean/agile transformations. People jump enthusiastically, enjoying the rush of sudden speed and the exhilaration of getting things done as a team, only to discover organizational gravity when they hit rock bottom.

If only we knew how to fly. In his acclaimed survival manual "The Hitchhiker's Guide To The Galaxy," Douglas Adams points out that there is an art, or rather, a knack to flying. The knack lies in learning how to throw yourself at the ground and miss.

To be able to do that, you need power. And for that, you need to know a little bit about how to get it. You need to know about politics.

The political economy of lean transformations

Talking about the political economy of lean/agile transformations always brings a smile to my face. As a political economist turned computer programmer, turned delivery manager, turned project manager, and ultimately turned management consultant, I can talk for hours about this and not get bored.

Don't worry though, I'll give you the short summary. The very short summary in fact: All politics is a struggle for power. The political economy of lean/agile transformations then, looks at the effects of the redistribution of power in an organization.

Now, there's something special about power. To speak with Rosabeth Moss Kanter: "Power is a dirty word. It is easier to talk about money and much easier to talk about sex than it is to talk about power. People who have it deny it; People who want it do not want to appear to hunger for it; And people who engage in its machinations do so secretly."

Let's open up about power for a bit. And while we're at it, let's lighten up about power as well.

And let's begin with the end in mind: To learn what you need to know about power to become a more effective change agent, you don't have to read Machiavelli. You just have to read this book: "Power, Why Some People Have It - And Others Don't," by Jeffrey Pfeffer. In that book, the Stanford Professor of Organizational Behavior provides ten tips to help you wield power like a Jedi with a light saber:

- Mete out resources.

- Shape behavior through rewards and punishments.

- Advance on multiple fronts.

- Make the first move.

- Co-opt antagonists.

- Remove rivals–nicely, if possible.

- Don’t draw unnecessary fire.

- Use the personal touch.

- Make important relationships work–no matter what.

- Make the vision compelling.

Why should you learn about power? You should learn about power for three reasons:

- First, power is a tool. A sharpened saw in stead of a dull one. By knowing about power, you can help organizations change faster, with less risk of organizational gravity wreaking havoc on your hard work. All tools can be used for evil as well as good. It’s the same with power. Most of us that “don’t like to play games” are just afraid we’ll lose. That’s not principled. That’s chickening out. Wielding power purposefully allows you to be more effective as a change agent. Don't fight the power, grab it!

- The second reason you should learn about power is that your opponents have learnt how to wield it to create and protect the status quo. Rest assured that as you enter an organization, it will be structured in such as way as to conserve the status quo. It’s a natural state for organizations. Well, sort of. In reality, all systems are in a state of continuous flux. Which is why all the politicking occurs. It is needed to maintain the status quo. It’s also needed to topple it.

- The third reason you should learn about power is because of what happens to power in a successful corporate lean/agile transformation. Transforming organizations from a traditional to an lean/agile structure entails a democratization of power in the organization. From management to teams, from IT to business, from top to bottom. Power gets redistributed from the elite to the masses. It's a radical democratization of decision making power. Such redistributions are generally met with a combination of enthousiasm and resistance. Both are understandable.

But there is another reason companies are remarkably resistant to change. This has to do with organizational gravity.

The concept of organizational gravity

The concept of organizational gravity comes from Mike Cohn. In his book “Succeeding With Agile,” Cohn describes the tendency of an organization to slowly, but surely, veer back to it's original state. Old habits die hard.

Organizations are structured to maintain the status quo. To escape that, you have to exert a lot of power. The larger the organization, the more power you'll have to exert. If you don't exert enough power, whatever you launched will either come crashing down or at best achieve orbit.

Some real life examples

Let's talk about some real life examples for a minute.

Way back when I was still a Project Manager struggling to convince management that an agile way of working would yield better results, I got called into the office of the head of Project Management. He showed me a letter from one of our most important clients. The letter said we would loose the contract if we did not improve within three months. "That's your assignment," the head of Project Management told me, "do whatever it takes to make it right so we don't loose the client." And I did. What it took, was some remedial team building and the introduction of an agile way of working. Within six months, the client sent us another letter. This time, it was a signed reference for marketing purposes. A dramatic reversal of customer satisfaction! All thanks to adopting an agile way of working. They kept improving on that way of working after I left and today have a rock solid reputation for delivering high quality software to millions of users. This then, is an example of an organization truly overcoming organizational gravity.

More recently, I consulted with a company that wanted to deliver faster, more relevant software to production with higher quality at lower cost. They'd done a lean transformation already, and asked us to do an agile one as well. So we did. And it was a success! We helped the client create multiple agile teams simultaneously working on the same technology stack and worked with management to introduce a governance structure feeding those teams with a single corporate backlog. And then, the financial crisis hit home. The company had to cut costs fast. So they did the now obvious thing: They asked their agile teams for help. And the teams told management to fire half of them. So they did! How about that? You ask the turkey what to have for dinner for Christmas and his advice is to have turkey! That was the level of understanding the teams had gained from adopting an agile way of working. But, there's a sad end to this story. The shift from continuous improvement to cost-cutting, that is from Eastern lean to Western lean, destroyed employee loyalty to the company. The first to go off to greener pastures were the managers and team members instrumental in the initial change. Then, organizational gravity hit hard. Last I heard, the teams are being told what to do by management and have stopped thinking for themselves. Apparently, overcoming organizational gravity is not enough, you have to keep at it to avoid falling back down.

Overcoming organizational gravity

So, how do you overcome organizational gravity? And how can you make sure you keep at it to avoid falling back down?

Speed is essential. The faster you go, the faster you'll show results. The more results you show, the easier it is to maintain momentum and push for a real and lasting change. Also, speed sharpens your focus and facilitates flow. It hightens your senses and prevents you from cruising along without paying close attention to what you're doing. Just like driving a supercar on a racetrack.

Trouble is, you're not actually on a racetrack in a corporate lean/agile transformation. For starters, there usually a lot more cars on the road. And they're not all supercars. They drive at different speeds. Worse, they follow different rules. Worse still, they might not be going in the same direction.

So a corporate lean/agile transformation is more like driving a supercar through heavy cross-town traffic. If you want to do that at speed, it's hard to keep going without accidents. It's impossible to do that without breaking the rules.

Breaking the rules is essential. Or rather, using and bending the rules so they work in your favor. To cut through cross-town traffic in a supercar at speed, all you need is flashing lights, a siren, and a badge. In a corporate setting, that's a sense of urgency, vocal executive support, and power. However, if you're using and bending the rules in your favor, you'd better have a good reason and a great sense of direction. If not, you'll lose popular support really quickly.

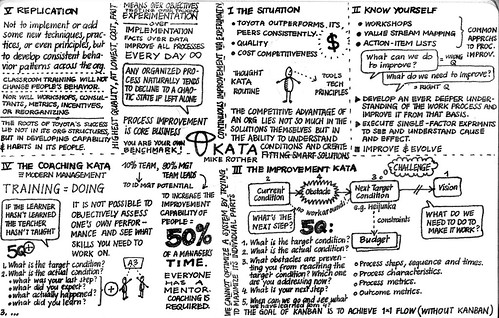

Navigation is essential. If you don't know where you're going, any road'll take you there. So you have to know where you're going. Or rather, where you currently want to go. And then get everyone to go along. A great and proven way to do just that on all levels in a corporate setting is applying Toyota Kata:

- What is the target condition?

- What is the actual condition?

- What obstacles are preventing you from reaching the target condition? Which one are you addressing now?

- What's your next step?

- When can we go and see what we have learned from taking the next step?

What we call lean/agile today, resulted in large part from answering those five questions consistently over time. As Mike Rother points out in his book "Toyota Kata," the roots of Toyota's success lie not in its organizational structures, but in developing capability and habits in its people. The competitive advantage of an organization lies not so much in the solutions themselves, but in the ability to understand conditions and create fitting smart solutions.

This points to an important, and in my opinion sorely missed, addition to the Agile Manifesto:

Experimentation over implementation.

Do something. See if it works. If it does, do more of that. If it doesn't, do something else. As opposed to think of something. Talk about it. Talk about it some more. Then talk about something else.

If you don't go fast, break the rules, and navigate like a pro, you're likely to go SPLAT! Avoiding a Surprisingly Painful Lean/Agile Transformation (SPLAT), is hard work.

It's hard work to keep up the pace. In a truly lean/agile organization, you're not just sprinting, you're doing back-to-back sprints without stopping. It's more like a marathon. Actually it's more like an ultra. To be able to do that, you must want it badly. And you must train. A lot.

It's hard to break the rules. Sometimes, this may get you fired. Like in the story Brian Marick likes to tell about a certain Scrum Master:

- An agile team was made to work in cubicles, like the rest of the company.

- Agile methods aside, cubicles are the "single worst arrangement of humans and objects in space for the purpose of developing software."

- The team proposed changing their workspace to an open one.

- Furniture Police turned them down.

- In response, the Scrum Master went to the office over the weekend. She disassembled the cubicles and changed the office layout to an open one. On Monday, she declared to the Furniture Police that "If the cubicles come back, you will have to fire me."

- They gave in.

But they could have just as well taken her up on her offer and fired her.

Hard work, hard work, hard work. Are there really no shortcuts? Well, no, not really. But you can speed things up a bit. Quite a bit in fact. Let's have a look at some of these "wormholes."

Wormholes to the rescue

A wormhole, or Einstein-Rosen bridge, is a shortcut through spacetime, much like a tunnel with two ends each in separate points in spacetime.

Start your lean/agile transformation small, but make sure to select a really important project. Preferably one with lots of risk and high pressure. This will allow you to start fracking the organization releasing the hidden energy reserves encased within.

Propose a ship-it day to show everyone the power of self-organization. Ship-it days are a fun way to foster creativity, allow people to scratch itches and get radical. They're also a wake-up call to management showing them what happens if they stop holding people back.

No one in their right minds should be against the disciplined application of common sense. And that's exactly what lean/agile is. In other words: Just do it. So if you can't get anyone to approve your lean/agile transformation effort, remember it's more blessed to ask forgiveness than permission. Get going, kickstart a never-ending cycle of continuous improvement, and merrily deal with whatever impediments you encounter to getting things done. Results don't lie!

So, now for constructing your parachute on they way down to overcome organizational gravity. You jump in without a parachute. How do you avoid hitting rock bottom? I have seven tips for you to help you do that.

7 powertips for smarties

- Be honest with yourself. See things as they are, not as you want them to be. Acknowledge your feelings, then use the scientific method to check their validity.

- Use social network analysis to map the distribution of power in an organization. Visualizing the flow of power makes it easy to tap into it.

- Use heat maps to identify the points of maximum leverage in an organization. Visualizing the distribution of power makes it easy to know where to start drilling for oil.

- Create a power matrix to determine who to influence.

- Show genuine interest in everyone you meet. You never know where they'll end up later. Make eye contact, let them talk first, ask open-ended questions, listen.

- Tap into the awesome power of the secretary or personal assistant. Get to know them. Treat them as you would their bosses.

- If all else fails: Run!

Summary

Do your cause and yourself a favor, and learn about power. Be mindful of organizational gravity and use any means possible to overcome it, be it the smart use of power, plain-old hard work, or a shortcut. If you can't beat them, or join 'em and then beat them from within, run! Apply for a job at Semco, Google, or Toyota, to name just a few truly lean companies. Or start your own. Don't settle for less! You deserve to work at an awesome company!